Irshad’s ability to challenge us to think deeply, act boldly, and lead with vulnerability, empathy and integrity has left an indelible mark on me as a leader and person.

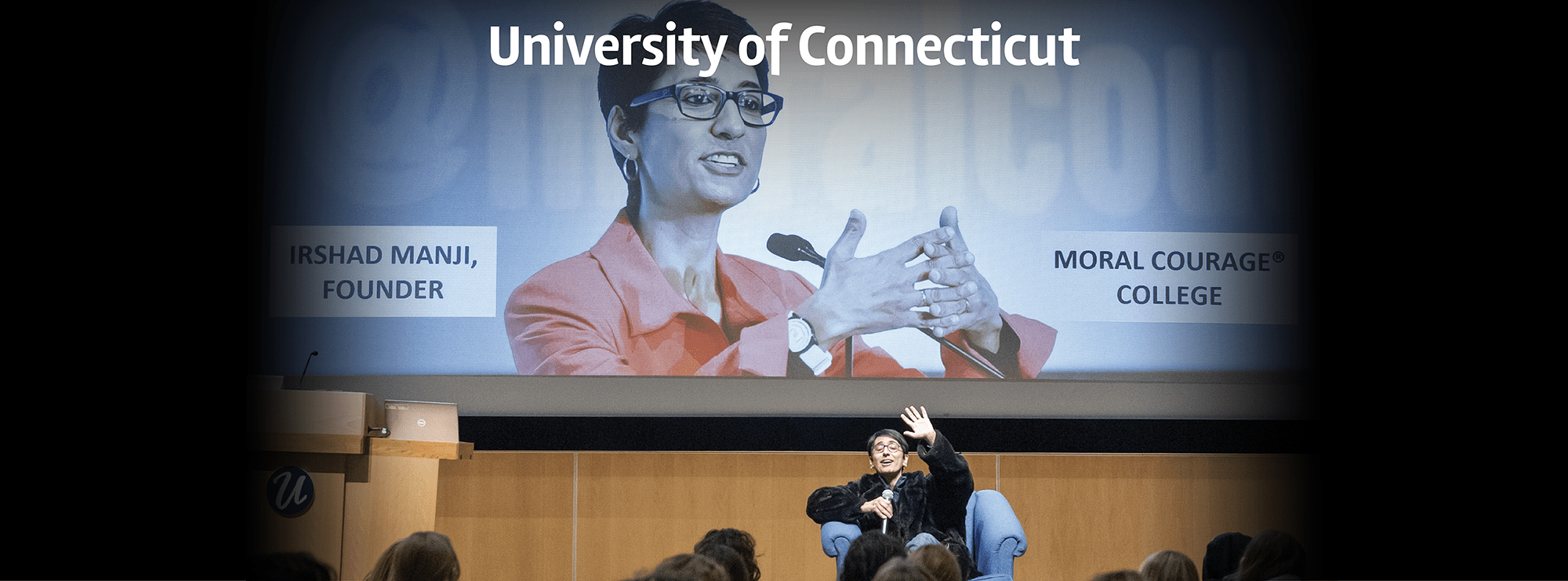

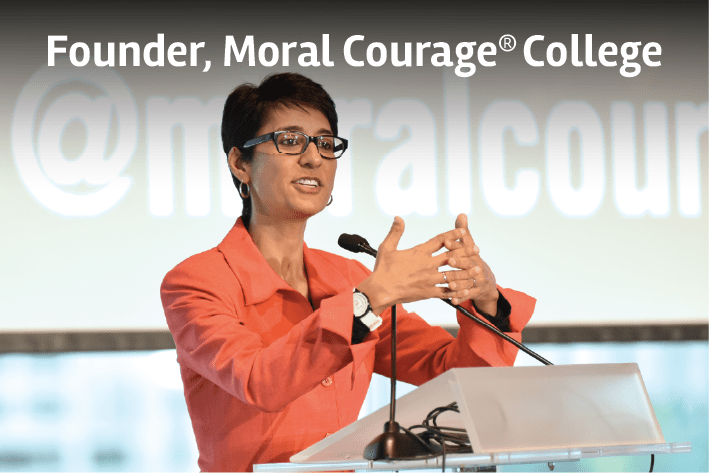

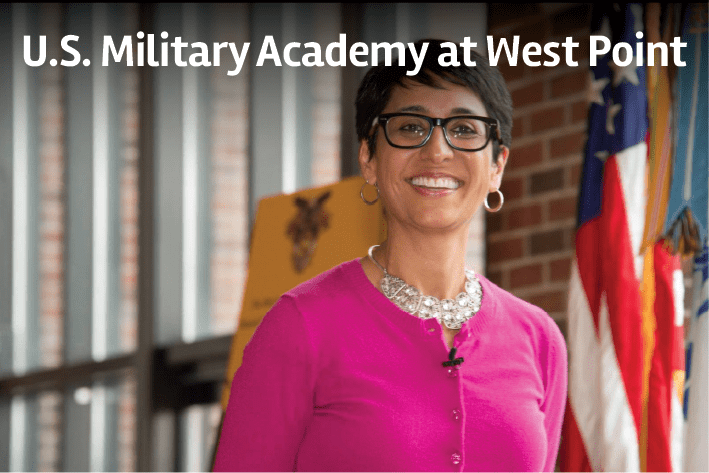

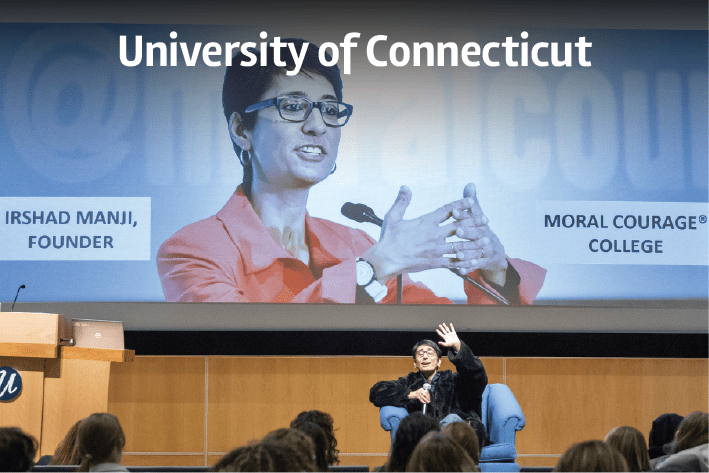

Prof. Irshad Manji:Moral Courage to Heal Divisions and Unite People

Acclaimed educator, New York Times best-selling author & founder of Moral Courage College

Dr. Shevon Davis-Louis

University School of Nashville

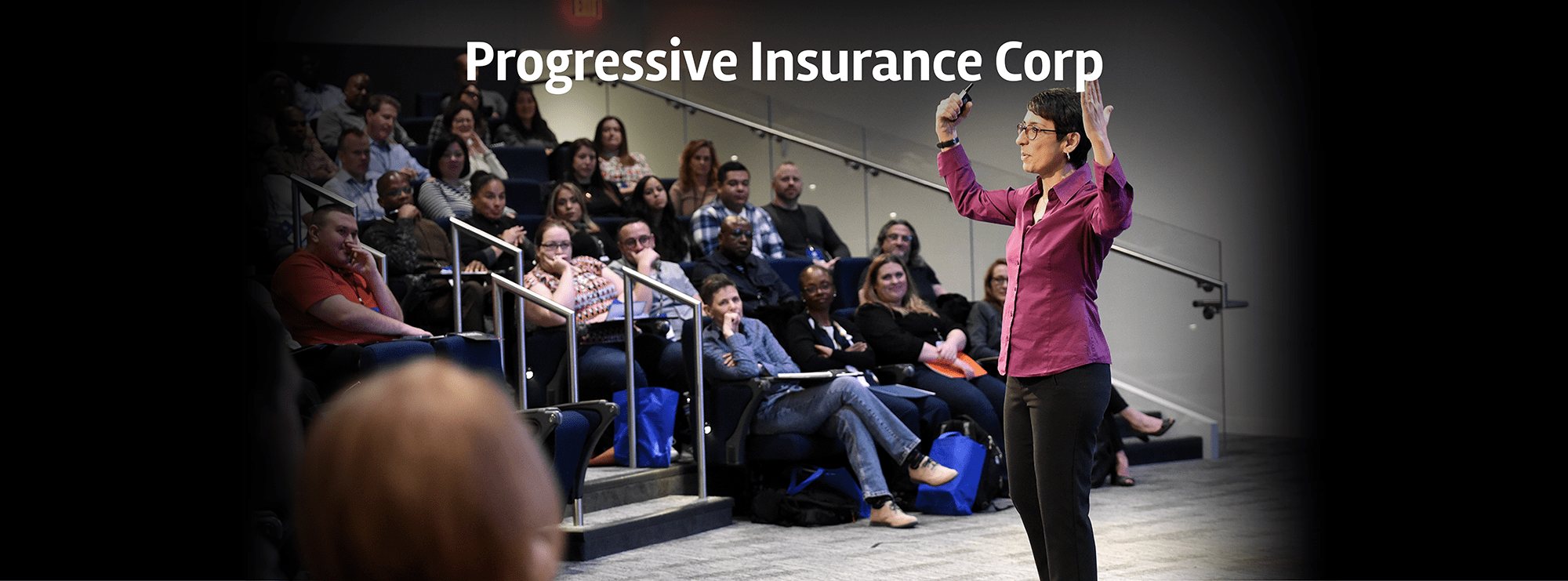

Every day, I use at least one of the Moral Courage skills that Irshad taught me and I’ve watched my colleagues do the same. In my 30+ years of evaluating impact, I can honestly say that her teachings are at the top.

Annemarie Schaefer

VP of Business Intelligence

Society for Human

Resource Management

Society for Human

Resource Management

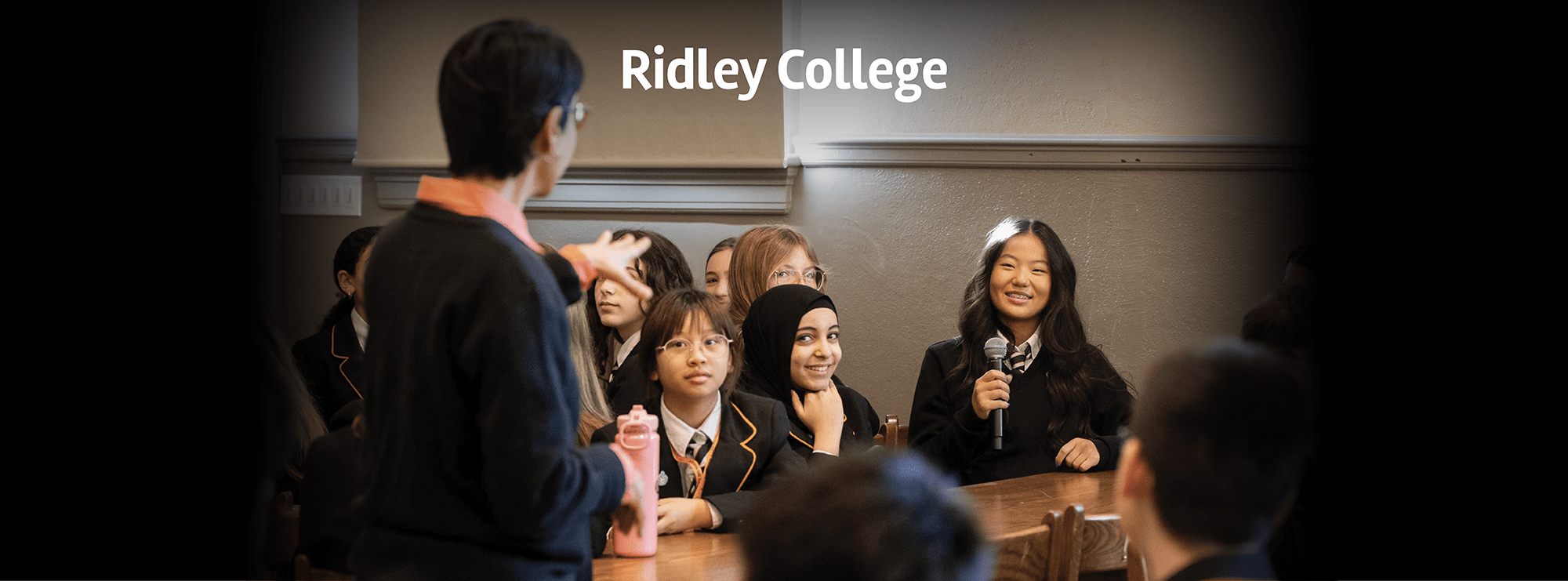

Irshad’s message electrified our students. Their standing ovation said it all.

Heidi Kasevich

The Nightingale-Bamford School,

New York

New York

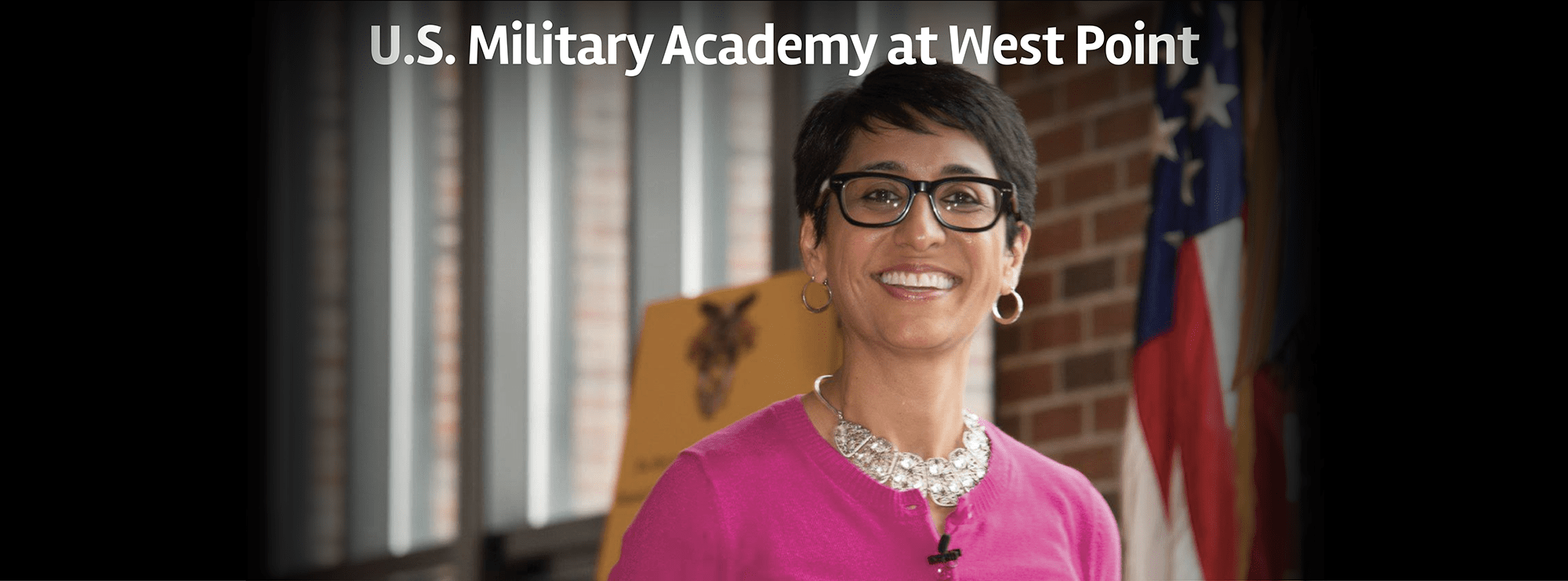

A single skill taught by Irshad is working wonders not only to improve dialogue with my officers, but also to de-escalate intense situations. It has now become a natural practice for me.

Deputy Chief Victor Green

Kalamazoo, MI Police Department

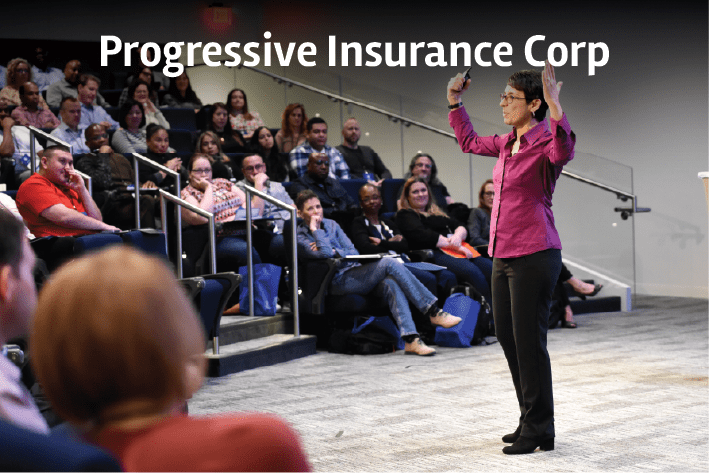

My biggest takeaway from Irshad is that empathy is essential to innovation. Sincere listening means learning something new, the key skill for leading truly transformative teams.

Marianne Copock

CEO, The Stelter Company

Anyone can talk about leadership but Irshad does it. She has inspired us to launch a Moral Courage Task Force that is student-led and solutions-oriented.

Rob Moore

Lawrence Academy, Groton, MA

Over the decades that we’ve been planning events, rarely have we seen such a captivating speaker.

Susan Engel

92nd Street Y, New York

Irshad spoke on-stage with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He, in turn, picked up on her central message — that asking questions is a basic human need — and he reinforced it with the audience. That is how dynamic a communicator Irshad is.

Sam Nappi

Common Ground for Peace